Hire the Best

You can spend all the time in the world on strategy sessions, competitive plans, innovation, and product development, but it all falls apart if you don’t have the right talent.

There’s a way to design an evidence-based, data-driven hiring strategy to boost your competitive edge.

That’s what Atta Tarki shares in his new book, Evidence-Based Recruiting. Atta is the CEO of Ex-Consultants Agency where he leads the private equity and venture capital practice. I reached out to ask him more about his research and new book.

Consider a Different Recruiting Philosophy

Evidence-based recruiting is rarely discussed. Many hire based on a “gut feel” and “cultural fit” but you say let’s all learn from Moneyball and take a different approach. Please share more about your philosophy of recruiting.

Most hiring managers talk a good game about wanting an “all-star in every position,” but deep down they don’t really mean it. If you probe a bit more, they will admit that they focus on “solid hires”—the foot soldiers of the corporate world. On the surface, this approach makes sense. All-stars are expensive and hard to find, and there is a widespread perception that trying to recruit for all-stars equates with “bad value.” But one of the key concepts I promote is that, in almost every setting, hiring managers would produce greater value by spending more resources on finding rare, star performers.

Hiring managers often justify their incremental approach to talent acquisition through the faulty assumption that a team’s value is created by solid, slightly-above-average workers. This view is usually rooted in the number of average performers versus star performers. Hiring managers believe that because star performers are so rare, they must only make up a small share of the entire value created. On the surface, this view seems to make sense.

But one of the key concepts I promote in my consulting work is that while stars are rare, they have an outsized influence on performance. In statistical terms, while the number of average vs. star performers follows a normal distribution, the value created by these individuals follows a power distribution.

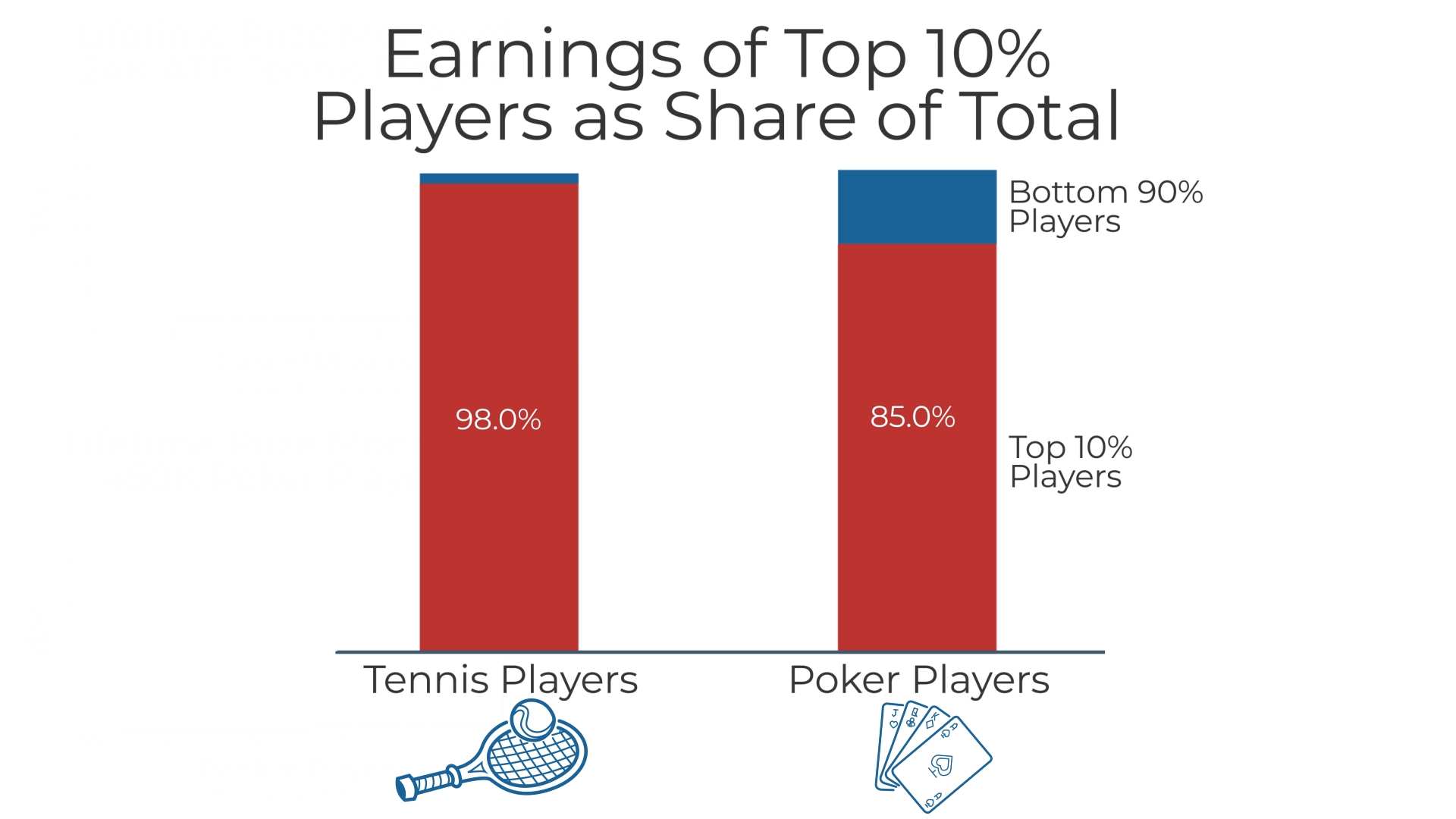

For example, I analyzed the lifetime prize money won by over 450,000 poker players and over 24,000 ATP tennis players. Since these datasets are quite large, they are more likely to be representative of the real-world differences of value produced by thousands of individuals in each profession. Yes, there are thousands of tennis and poker players who earn about the same amount of prize money, and these players seem to make up the vast majority of the individuals in these samples.

However, when you take a closer look at the data, you’ll see that in terms of the lifetime prize money, 98% went to the top 10% tennis players and 85% to the top poker players. These players were relatively few by the numbers, but they created the vast majority of the value.

In business terms, a superstar computer engineer is unlikely to write 100 times more code than an average performer. However, the quality of the code the super-star writes could result in billions of people using Google as opposed to AltaVista and other search engines.

Don’t Make these Hiring Mistakes

What are some of the major mistakes managers make in the hiring process?

Hiring managers don’t obsess about recruiting super-stars. Instead they spend too much time, energy and resources putting out day-to-day fires and trying to improve the performance of average or sub-par performers. I call this The Karate Kid approach. In this movie, Mr. Miyagi, through his superior coaching and mentorship skills, turns a kid who is a subpar performer into a superstar in nearly no time at all.

This can be contrasted to the Moneyball approach developed by Oakland Athletics General Manager Billy Beane. Despite enormous resource constraints, Beane developed a system that applies a razor sharp focus on finding and hiring the most under-valued, and thus relatively inexpensive, athletes on the market.

Most hiring managers think, “Sure, this worked out well in baseball, but it doesn’t apply to my industry.” They therefore go back to The Karate Kid approach. But The Karate Kid approach doesn’t really work if you want to build a team of stars.

Recruit Rock Stars

What are some of the best ways to recruit rock stars?

Be specific about what you are recruiting for. Many organizations recruit for traits that are too broad to be meaningful. We once worked with a company that was convinced that they could identify superstar candidates by testing for “high EQ.” But when we asked their interviewers what they meant by EQ, we received half a dozen definitions. It was unlikely that any candidate would excel in all those dimensions of EQ.

To illustrate the broader point, consider this hypothetical. Let’s say you are recruiting for someone who is athletic. Take a moment to define what that means to you and how you will measure “athleticism.” Don’t just walk into an interview and think you will know it when you see it. You need to define it first, and then evaluate candidates relative to that definition.

When ESPN had a panel of experts answer which sport required the most athleticism, they graded sixty sports on ten mostly physical qualities: endurance, strength, power, speed, agility, flexibility, nerve, durability, hand-eye coordination, and analytical aptitude. The panel included sports scientists on the Olympic Committee, researchers, an athlete who had successfully competed in both baseball and football, and sports journalists who spend their lives documenting the best athletes.

The term “athletic” can mean very different things in different sports. Even when selecting for athleticism, being specific matters. More precise definitions lead to a clearer understanding of the skills required. This will, in turn, enable your recruiting team to focus their efforts on finding you a superstar who spikes in the dimensions most important to you.

Conduct Structured Interviews

I love your structured versus unstructured interview discussion. For those who haven’t read the book yet, what advice do you have in this area?

One of the main arguments supporting unstructured interviews is that the interview questions and techniques need to be adjusted based on the perceived qualifications of each candidate. I am completely in favor of probing deeper where needed, of course. But if you’re winging every interview, are you really measuring each candidate to the same standard or applying arbitrary rules that change for every candidate? My advice is clear: if you want to improve the value that interviews provide, use structured interviews.

Many interviewers have a hard time separating how well a candidate presents during the interview from how well they will perform on the job. Interviewers are also affected by a variety of other biases. Most of us think it is unlikely that such biases will determine our impressions and decisions, but numerous studies show that even simple differences such as time of day or the applicant’s name can affect interview results. Structured interviews help recruiters to mitigate and override their biases by sticking to predetermined questions and deciding ahead of time which answers are good or bad.

Get Your New Hires Off to a Great Start

Any best practices that help ensure the individual gets off to a great start?

Many hiring managers who want to recruit rock stars begin by asking themselves what qualities the existing rock stars in their organization possess. They then decide to hire someone that displays all those qualities. On the surface, this makes sense, but it usually results in a Frankenstein approach—where hiring managers take attributes from multiple people in their organization and combine them into unattainable—and frankly monstrous—form. My advice to these hiring managers is to resist the temptation to replace Moneyball with Frankenstein.

This speaks to the true genius of the Moneyball approach. Billy Beane understood that he could not put together a lengthy list of requirements for the picture perfect candidate. Instead he focused on reducing the number of attributes he was recruiting for. Beane knew that he could not afford candidates who seemed picture perfect across a dozen criteria, so instead he recruited a number of candidates who were undervalued in one or two dimensions he cared about.

Reduce Bias

Bias, conscious or unconscious, is always an issue. How do hiring managers reduce it?

We’re incredibly lucky to live in a time when pretty much all hiring managers aspire to treat minorities or disadvantaged groups fairly. Just a generation ago, this was not the case. But we still have work to do. Deliberate exclusion is a rarity, but “second-generation” forms of bias persist—these are subtle, subconscious prejudices that frequently prevent hiring managers from identifying the most talented candidates.

Willpower is therefore not enough to defeat biases. The best interviewers don’t simply rely on self-restraint and a belief that they have pure, unbiased intentions. Rather, they design the candidate vetting process in a way that reduces the chances of them being exposed to information that may bias them. Structured interviews are among the best tools in this regard, especially if you define in advance what constitutes a good or poor response to your interview questions. If a candidate is providing you a response that you beforehand defined as “good,” but in the moment you are still dinging the candidate, you might want to ask yourself “Why is that? Is there a remote possibility that I’m biased?” If there is even a 1% chance in your mind that this might be the case, I recommend that you should consider abstaining from taking part in the hiring decision.

Finally, I highly recommend removing veto power from most interviewers. It’s OK if the ultimate hiring manager has veto power since the candidate will be reporting to them, but make it explicit that a candidate does not need to receive a unanimous vote to receive an offer. When you have multiple interviewers, the odds grow that a stellar candidate gets turned down due to illogical reasons, or the specific concerns of one individual—which may not be very relevant at all for the actual position being filled.

If you find that hard to believe, consider the following thought experiment:

Imagine a candidate is interviewed by five hiring managers and each of these hiring managers has a one in six chance of having some sort of illogical bias that prompts them to reject a qualified candidate. The biases of the hiring managers are independent of each other. What are the chances of a qualified candidate being rejected due to illogical bias if:

- Any of the five hiring managers has veto power—that is, the candidate needs five votes to get hired?

- The candidate needs three of five votes to get hired?

Simple math shows that the answers are:

- When any of the hiring managers has veto power, and therefore all five hiring managers need to agree, there is an approximately 60 percent chance the candidate gets vetoed illogically.

- When three of the five hiring managers need to agree, there is approximately a 4 percent chance the candidate gets vetoed illogically.

What are some best practices in working effectively with recruiters?

A number of hiring managers express their frustration to me over the fact that their recruiters have not yielded enough quality candidates. In trying to be helpful, I often ask these hiring managers questions to try to understand what specific activities their recruiters could undertake to yield better results. I often find that the hiring managers know very little about how their recruiters are trying to find them great candidates. One standard argument tends to be, “I don’t care how the results are produced, just as long as I get the right candidates.”

Some of these hiring managers end up telling me that it’s just the recruiter they worked with who doesn’t care or isn’t competent. In most cases, I need to take those recruiters under my wing (even if they don’t belong to my organization) and help the hiring manager take a step back. For what other part of your business would you think about your key success levers the same way?

If your manufacturing line stops working would you simply think, “I don’t know why they are not producing more gadgets and what the problem is. I will just keep telling them that I want better results and hope they will get there”? What if the problem persists for two consecutive days? How about if it persists for weeks, months, or years? How would you treat a similar issue with your accounting processes, with your marketing results or your sales team drivers? So why would you treat recruiting any differently?

If your manufacturing line stops working would you simply think, “I don’t know why they are not producing more gadgets and what the problem is. I will just keep telling them that I want better results and hope they will get there”? What if the problem persists for two consecutive days? How about if it persists for weeks, months, or years? How would you treat a similar issue with your accounting processes, with your marketing results or your sales team drivers? So why would you treat recruiting any differently?

The vast majority of recruiters I have worked with do care and are competent. They just face unrealistic expectations from hiring managers—for example, that a recruiter should be able to split their time on 30 or more openings, work without the tools they need to be successful, not have the budget to add more stars to the recruiting team and still produce stellar results. I understand that some of these hiring managers don’t make budget decisions. However, they can still get more out of their recruiters by applying a collaborative approach. Instead of demanding results by asking the recruiters to do more of everything, take a moment to understand the trade-offs that the recruiters face in recruiting for your role. If they are trying to find you a candidate through four different channels, it’s unlikely that all these channels are as effective. I get it. “You never know, a good candidate could come from a variety of sourcing strategies.” However, no one has unlimited resources, and whether you want it or not your recruiters can dedicate only so many hours to your search. The only question is, which of these strategies do you expect to be most productive? Understand this and help your recruiters prioritize the most productive activities.

For more information, see Evidence-Based Recruiting.