The Future of Work

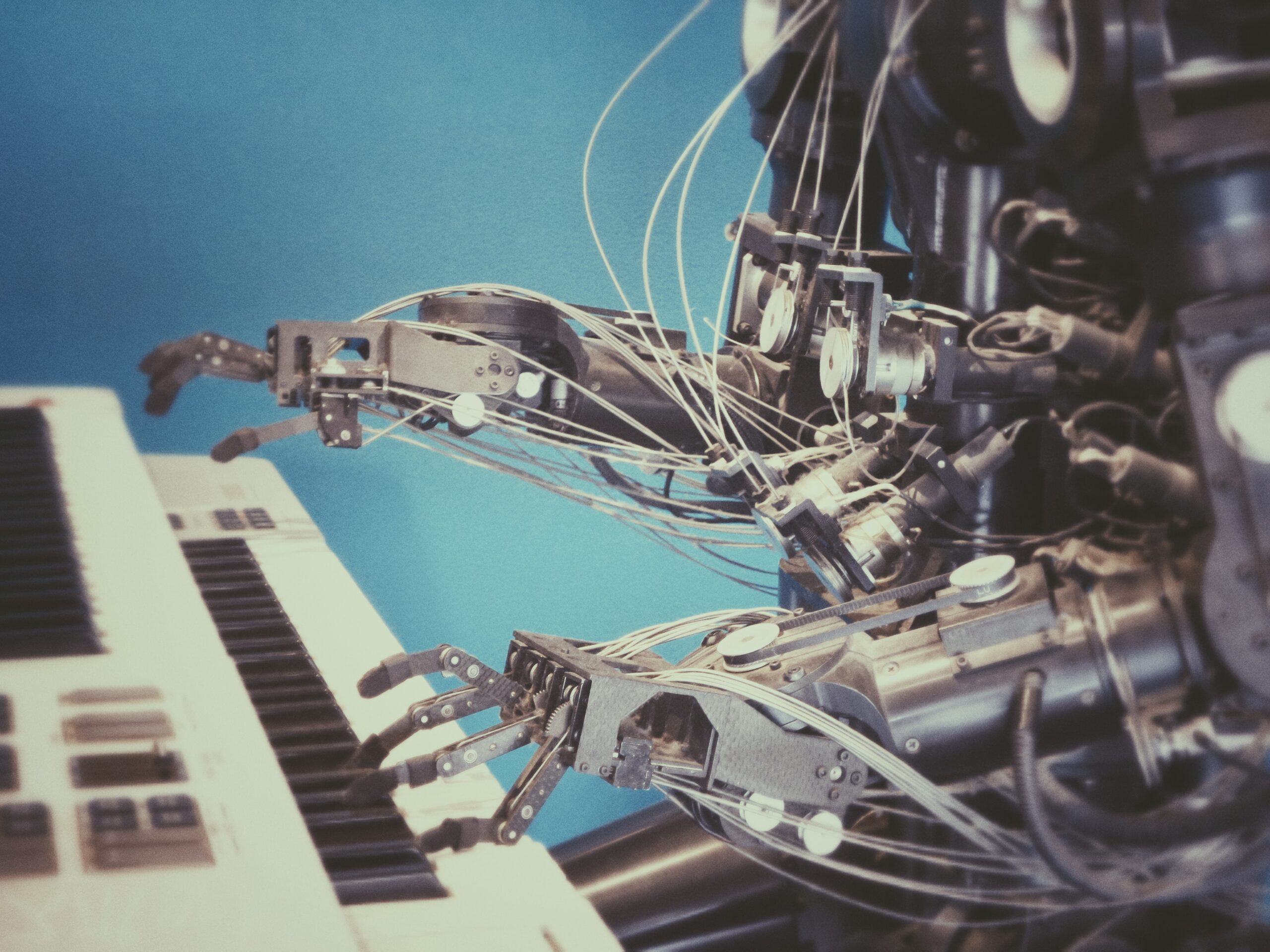

I’m often asked questions about the future of work. Will the machines takeover? How long until the human race declines? And how many jobs will go away?

One new book that thoughtfully approaches these topics of how we will work symbiotically with machines and how we can all evolve to benefit together is HUMAN/MACHINE: The Future Of Our Partnership with Machines.

I recently spoke with Olivier Blanchard, one of the co-authors.

What’s your general view of machines and robots and the future? Is the apocalypse coming with robots taking over or do you take a hopeful view?

Machines and robots are ultimately tools designed to serve mankind. Whether they help farmers plant and harvest crops faster and on a larger scale, or they help people struggling with medical challenges live more independent lives in their own homes, the impact of machines and robots on society is always going to be a net positive. The trick is to make sure that when machines and robots displace humans in certain types of occupations, those displaced individuals are able to find new occupations that will either be just as good for them or better.

I think that the robot apocalypse, while possible for some categories of jobs, is far from a foregone conclusion. If we manage the growth of smart automation properly, and plan for it adequately, it can be relatively painless.

What jobs are most at risk?

You could argue that all jobs are at risk: Machines can already analyze data, pick stocks, make decisions that touch on operational efficiency and logistics, sift through resumes and make hiring decisions, etc. – meaning that they can already perform key business management functions. Machines can prepare meals now. Cars will soon be able to drive themselves. Security robots already patrol malls and streets. Delivery robots might be delivering your next package. Automation is everywhere, and that trend is going to accelerate in the next decade.

Having said that, robots and automation tend to focus on performing specific tasks rather than jobs. This means that the more task-complexity a job has, the more difficult it will be to automate. Think, for example, of the difference between a chef and a fry cook: The chef manages the entire kitchen, and performs hundreds of different tasks, many of them simultaneously. A fry cook specializes in a very small series of specialized tasks. Therefore, the fry cook’s job can more easily be automated (think fry cook robot or a frying machine) than the chef’s. That insight alone gives us a pretty good glimpse into which jobs are more at risk of being automated than others.

Generally, any job that consists of a small number of repetitive tasks is likely to be automated first. That is why assembly line jobs like turning a screw, punching a hole, making a cut are easily replaced by automation. In an office environment, tasks like sending out invoices, processing payments, and managing payroll can also be automated fairly easily. But increasingly, machine learning and artificial intelligence are beginning to also automate more complex tasks – like project management, customer service roles, data analysis, logistics management, and content creation – so no job is entirely safe from automation in the long term. Personal assistants may become mostly digital. Same with accountants and paralegals. We’ll have to wait and see how things shake out. What I do know for sure is that job descriptions and employment statistics are likely to look very different thirty years from now, so no matter what happens, we are on the cusp of a radical transformation when it comes to the future of work.

What ways can aspiring leaders prepare and futureproof their career?

A good place to start is to take the initiative: You can either wait for your employer to replace you with one or several automation solutions, or you can incorporate automation into your workflows in order to become more productive. This choice is at the heart of the replacement vs augmentation equation.

Think of it this way: An employer may already be looking at the cost/benefit of replacing you with machines. (It doesn’t matter if you are working in a package sorting center or a marketing department.) The more you are able to increase your productivity, the more you increase your value. If you just come to work and do your job like everyone else, you probably aren’t creating as much value for your company as if you started offloading your more basic and repetitive tasks to bots and automated solutions, and suddenly became 2-3x more productive than your coworkers. So a good strategy is to learn about what automation solutions are out there, start experimenting and incorporating them into your workflows, and augment yourself using these technologies instead of rolling the dice and letting your employer make those decisions for you.

How do leaders strike the right balance between automation and augmentation?

When you are a business leader, you sometimes have to make hard choices. Sometimes, even if you wish you could adopt a 100% augmentation strategy for your workers, you still end up having to settle for a 70:30 ratio of augmentation:replacement, because that’s what makes financial and operational sense. The reality is that if a job or function can be automated, and there is no compelling reason not to do it, then it probably should be. Particularly if automating functions that need to be will make your company more competitive and more profitable. So the trick isn’t so much to strike the right balance between replacement and augmentation – as a company that approaches this problem competently will usually strike the right balance – but rather to make sure that humans being replaced by machines aren’t merely discarded and tossed aside.

For starters, companies should be careful not to contribute to growing unemployment, as the stress it could cause on the local economy and economy at large could come back to haunt their bottom lines. Secondly, developing lifelong loyal employees is preferable and probably more cost-effective than the constant churn and friction of hiring and layoff cycles. Employees being displaced by machines should therefore, whenever possible, be retrained or reskilled, and moved to adjacent positions in the same company. Some of these positions might be entirely new categories of jobs (robot maintenance technician, for example), or they might be existing ones. A third option may be for the employer displacing these workers to help retrain them, then partner with local or state agencies to help them find job opportunities elsewhere. The point is that leaders should consider the unintended consequences of their decisions, and continue to invest in people even if their business is also investing in automation. This type of thinking will pay off in the end.

You cover various industries and how they should prepare for the age of human-machine partnerships. Let’s jump to higher education. What’s your view of how education should approach the coming age?

As much as I love traditional education, I think it’s time to start focusing on preparing workers and leaders for an age of smart automation and ubiquitous AI. To some degree, I feel that education and training are now very different tracks – equally important, but separate from one another. More than ever, we are going to need emotionally intelligent, self-aware, empathetic, creative thinkers to work alongside machines and steer business and policy decisions toward positive ends. That means studying art, literature, history, philosophy, languages, science, and math. But by the same token, tomorrow’s leaders also need to be taught specific skills, such as how to work alongside AIs and machines, how to effectively partner with them, how to manage organizations in the era of human-machine partnerships, how to motivate, support, and inspire human workers, and how to make ethical decisions in an age of cutthroat pragmatism.

What we will need in the coming decades aren’t just more competent leaders but also leaders who exemplify the best qualities that humans can hope for. The best partner for an increasingly better machine is an increasingly better human. Higher education should play a role in producing better humans.

What are the responsibilities companies may struggle with over the next few years?

Aside from finding the right balance between augmentation and replacement, ensuring that business cultures remain ethical and human, and minimizing unemployment as a result of job displacement, one of the biggest struggles that organizations will face in the coming years will be the uneven nature of automation solutions: While some are fairly mature now, others won’t be for some years to come, and so expectations about how well automation works, and whether or not some solutions will solve more problems than they cause, will be a source of friction for many companies that begin to transition to an automated future. It will take some trial and error, work, and a lot of patience to get there. One of the key differentiators between organizations that will adjust quickly and organizations that will struggle to adjust will be their ability to partner with the right technology vendors. Special care should be taken by companies to identify technology vendors, test their solutions, and sort the good from the not so good.

What are some of the mistakes that leaders are making when thinking of our future with machines?

Maybe a better way to address that question is to list a few potential mistakes that leaders should be aware of, so that they won’t make them themselves.

The first mistake to look out for is not adequately differentiating between task automation and job automation. That miscalculation could cause some businesses to invest in the wrong technologies for the wrong reasons and miss out on the real benefits of smart automation.

The second mistake to look out for is not properly weighing the notion of augmentation versus replacement. Too many leaders will lead with human replacement, because they think of automation mostly as a replacement scheme, and they will miss out on opportunities to use automation to augment their workers and improve their productivity and value.

The third mistake is likely to be a lack of investment in employee training. Transitioning to an internal operational model of human-machine partnerships will require new skillsets, the adoption and refinement of new workflows, processes and procedures, new collaboration paradigms, and so on. Without adequate training and structures in place, human workers may struggle to adapt to change, and the organization may fail to run as smoothly as it should. Training and employee development will be key to the success of a company’s automation transformation.

The fourth mistake that I want to caution business leaders about is the instinct to delegate automation knowledge and technology fluency to IT or a CTO role. Every business leader, from the CEO on down to team leads should cultivate a fluency with automation technologies, best practices, and specific solutions. Any business leader who doesn’t make the effort to truly understand how and why automation should be used across every layer of the business they are charged with running is doing themselves and their organization a dangerous disservice.

For more information, see HUMAN/MACHINE: The Future Of Our Partnership with Machines.